While COVID Raged, Another Deadly Threat Was On the Rise in Hospitals

LA Times Article - Written by Emily Alpert Reyes

As COVID-19 began to rip through California, hospitals were deluged with sickened patients. Medical staff struggled to manage the onslaught.

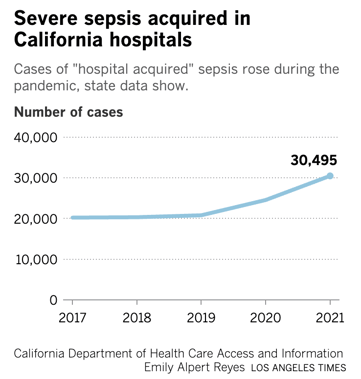

Amid the new threat of the coronavirus, an old one was also quietly on the rise: More people have suffered severe sepsis in California hospitals in recent years — including a troubling surge in patients who got sepsis inside the hospital itself, state data show.

Sepsis happens when the body tries to fight off an infection and ends up jeopardizing itself. Chemicals and proteins released by the body to combat an infection can injure healthy cells as well as infected ones and cause inflammation, leaky blood vessels and blood clots, according to the National Institutes of Health.

It is a perilous condition that can end up damaging tissues and triggering organ failure. Across the country, sepsis kills more people annually than breast cancer, HIV/AIDS and opioid overdoses combined, said Dr. Kedar Mate, president and chief executive of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement.

“Sepsis is a leading cause of death in hospitals. It’s been true for a long time — and it’s become even more true during the pandemic,” Mate said.

The bulk of sepsis cases begin outside hospitals, but people are also at risk of getting sepsis while hospitalized for other illnesses or medical procedures. And that danger grew during the pandemic, according to state data: In California, the number of “hospital-acquired” cases of severe sepsis rose more than 46% between 2019 and 2021.

Experts say the pandemic exacerbated a persistent threat for patients, faulting both the dangers of the coronavirus itself and the stresses that hospitals have faced during the pandemic. The rise in sepsis in California came as hospital-acquired infections increased across the country — a problem that worsened during surges in COVID-19 hospitalizations, researchers have found.

“This setback can and must be temporary,” said Lindsey Lastinger, a health scientist in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Division of Healthcare Quality Promotion.

Physicians describe sepsis as hard to spot and easy to treat in its earliest stages, but harder to treat by the time it becomes evident. It can show up in a range of ways, and detecting it is complicated by the fact that its symptoms — which can include confusion, shortness of breath, clammy skin and fever — are not unique to sepsis.

There’s no “gold standard test to say that you have sepsis or not,” said Dr. Santhi Kumar, interim chief of pulmonology, critical care and sleep medicine at Keck Medicine of USC. “It’s a constellation of symptoms.”

Christopher Lin, 28, endured excruciating pain and a broiling fever of 102.9 degrees at home before heading to the Kaiser Permanente Los Angeles Medical Center. It was October 2020, and the hospital looked “surreal,” Lin said, with a tent set up outside and chairs spaced sparsely in the waiting room.

His fever raised concerns about COVID-19, but Lin tested negative. At one point at the emergency department his blood pressure abruptly dropped, Lin said, and “it felt like my soul had left my body.”

Lin, who suffered sepsis in connection with a bacterial infection, isn’t sure where he first got infected. Days before he went to the hospital, he had undergone a quick procedure at urgent care to drain a painful abscess on his chest, and got the gauze changed by a nurse the following day, he said. Such outpatient procedures aren’t included in state data on hospital-acquired sepsis.

Someone with sepsis might have a high temperature or a low one, a heart rate that has sped or slowed, a breathing rate that is high or low.

It can result from bacteria, fungal infections, viruses or even parasites — “and the challenge is that when someone walks into the emergency department with a fever, we don’t know which of those four things they have,” said Dr. Karin Molander, an emergency medicine physician and past board chair of Sepsis Alliance. Treatment can vary depending on what is driving the infection that spurred sepsis, but antibiotics are common because many cases are tied to bacterial infections.

This article was originally posted to LA Times on February 5, 2023